-

Oasis of mezcal: reforestation, water harvesting and agave cultivation in Oaxaca´s Valles Centrales

Agua del Espino, Oaxaca Mexico

2022

Humble Beginnings

The town of Agua del Espino, situated alongside the now dry bed of the Prieto river, is modest in comparison to the surrounding land. Established in 1936, nearly half of the ejido’s 2,071 hectares were designated as communal. In its early days, a plethora of vegetation dappled the ejido’s rolling hills. Agave, growing in abundance alongside shrubs and weeds, was locally sourced in these communal mountains.

Despite mezcal´s processes, which require the entire plant to be harvested, residents never worried about depleting the supply. Within this idyllic ejido, distillation techniques were lovingly passed down from one generation to the next, preserving the artistry and craftsmanship of mezcal production. The drink is a living testament to the enduring power of tradition, where the locals embrace mezcal as more than just a drink—it is a symbol of joyous celebration, deeply intertwined with the fabric of their community.

Into the Present

The growing international popularity of mezcal has brought great change to the region of Agua del Espino. Driving forces of economic opportunity have incentivized agave cultivation, leading old growth patterns and existing farmlands to be disrupted in favor of geometric monoculture agave patches. As exports rose, more residents entered the cultivation business, and fewer workers left for the city or el Norte. More homes and plantations sprung up as Agua del Espino became more populated. In other words, the ejido’s economy was improving.

While these current farming practices have brought economic prosperity to Agua del Espino, they are hardly sustainable. The communal land in particular has faced significant degradation; after several years of monoculture planting and livestock grazing, much of the soil has lost its fertility. The Prieto river, which once flowed year round, now rarely manages to trickle during the rainy season, while farmers are joyful for clouds that never rain.

Moving Forward

The ejido's true power lies in the unbreakable bond within its community. Living and working together under the concept of shared land, the townspeople form a resilient collective that wields a remarkable strength to bring about substantial and positive transformations. On the 14th of January 2023, the townspeople convened at the Agencia building to address the concerning degradation of the landscape. Attentively, the farmers listened to proposals put forth by Enlace Foundation, ReThink Foundation and the Instituto de la Naturaleza y Sociedad de Oaxaca (INSO), aimed at initiating the crucial process of environmental restoration. With unanimous agreement on the following proposals, the farmers are hopeful that implementing these changes will lead to the recovery of their soils, increased access to water, better crop yields, and the complete restoration of the Prieto and its aquifers.

Following workshops with students and professors from the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 2018 and the University of Toronto in 2019, the Enlace Foundation and the ReThink Foundation have embarked on a series of projects aimed at revitalizing Agua del Espino. Thanks to the invaluable support from Harvard University's David Rockefeller Center of Latin American Studies (DRCLAS), local schools, and INSO, many of these projects have already begun.

Surveying the Land

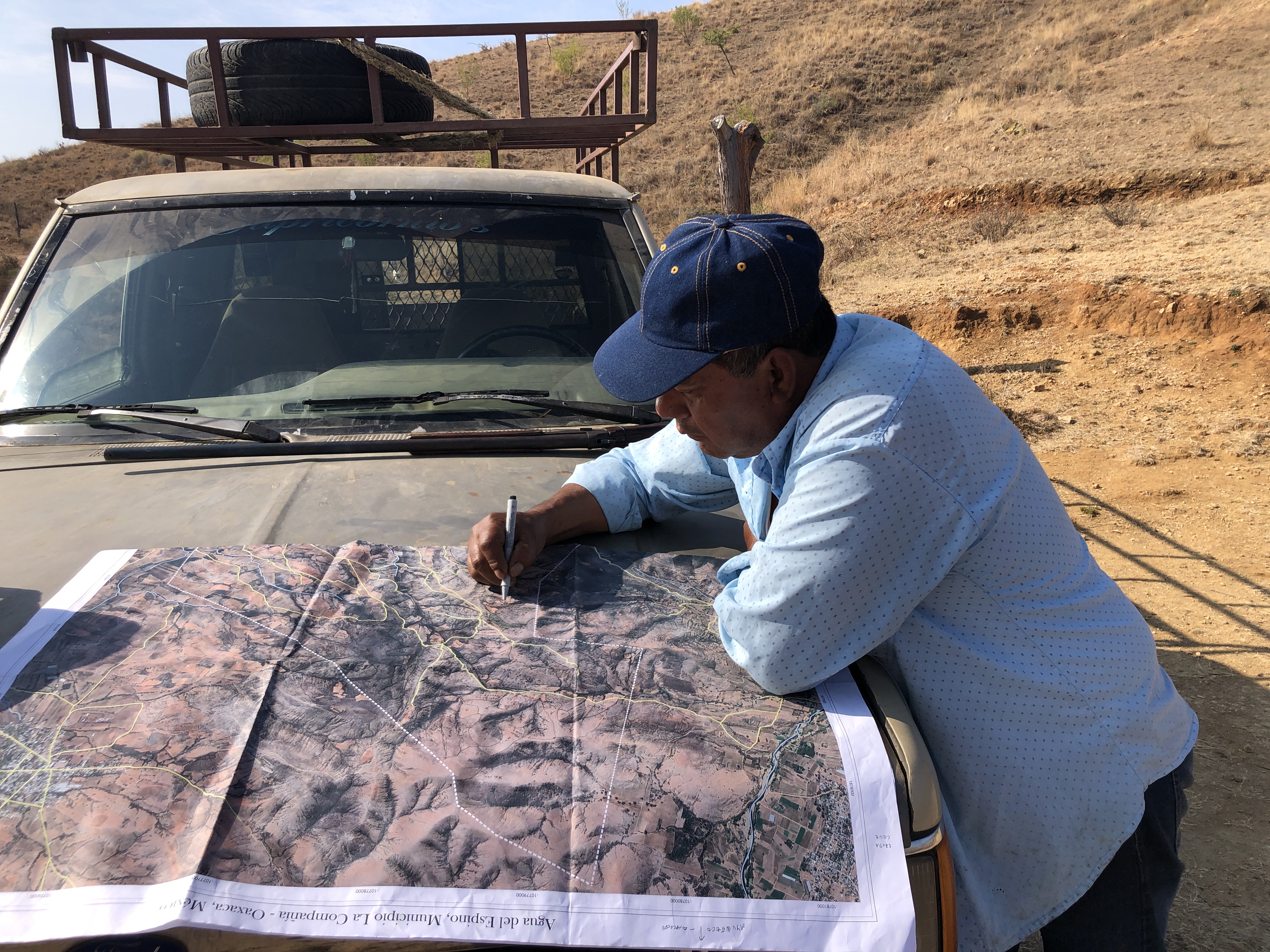

In May of 2022, Enlace Foundation spearheaded an extensive mapping and land surveying expedition. Up until this point, the precise demarcations of land assigned to villagers, and areas called agostadero or communal land in Agua del Espino existed only in the collective knowledge of the townspeople, as the area had never been concretely mapped before.The possession of this collective knowledge, combined with their status as an ejido, stands as a powerful testament to their strength in community, culture, and generational wisdom. However, as this invaluable knowledge has begun to dissipate with the younger generation, there is an increasing need to record and preserve this vital wisdom for the future.

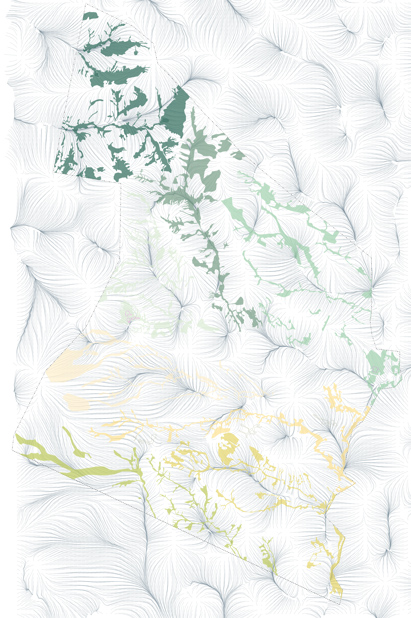

Armed with a large format printed satellite map, Elisa Silva of Enlace and Comisario Tirmo García embarked on a journey that spanned several days, carefully marking out boundaries by hand. These long days of walking and mapping not only shed light on the patterns of land ownership in the area but also unveiled the delicate patterns of vulnerable greenery. Notably, surviving patches of lush growth were intricately tied to paths of rainwater trickling down the landscape, particularly thriving along the north faces of the peaks, where the oblique sun rays hit the sloped ground with less intensity compared to their sun-drenched southern counterparts.

Over the years, satellite imagery has documented the gradual depletion of greenery, highlighting the magnitude of the ecological impact. However, the recent mapping expeditions led by Silva and García have offered a more comprehensive view of the landscape, revealing previously unknown vulnerabilities exemplified by an alarming overlap of newly-claimed private land and the sparse remnants of once-lush vegetation. Market pressures to cultivate more land are motivating a de-facto privatization of the communal lands. Such land grabs place these fragile ecosystems at even greater risk; continued unrestricted land use may further threaten the survival of these precious green patches.

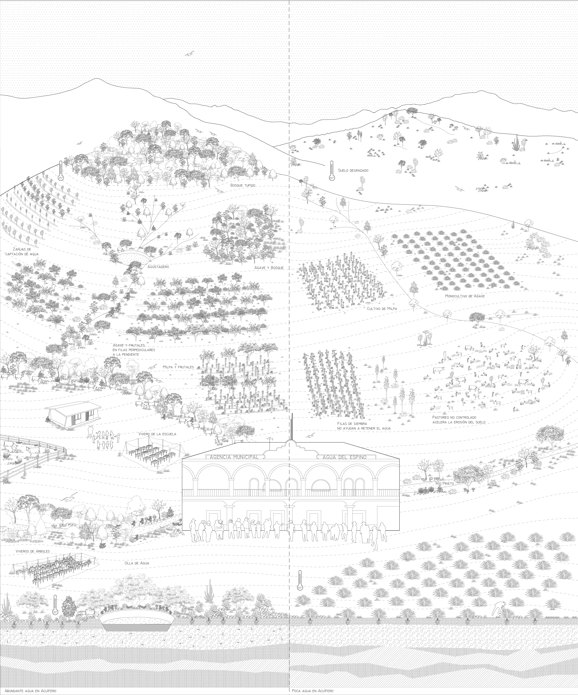

Water Catchment

Among the notable initiatives spearheaded by Enlace, ReThink, and their partners, the digging of a new water basin marks the beginning of this process. Envisioned to capture and aid the filtration of rainwater into the aquifers, this method of water catchment proves to be innovative because of its economic efficiency. It also draws inspiration from existing practices in the area, albeit present in great moderation.

By creating several new basins strategically scattered throughout the region, the Enlace Foundation aims to extend the retention period of rainwater within the landscape, reducing rapid evaporation and runoff while simultaneously encouraging plant growth. Further, it will lead to decreased temperatures, mitigating the impact of scorching heat waves during dry periods.

The significance of these basins extends beyond immediate ecological improvements. As water filters down to replenish the large aquifers, the town is assured of a sustainable water source, even during the harshest dry seasons. Access to plentiful water ensures the townspeople's well-being, safeguarding agricultural practices, supporting livestock, and securing the basic needs of everyday life.

Reforestation

The reforestation initiative seeks to breathe new life into the landscape by reintroducing a plethora of native plants, such as Guaje, Guamuche, Copal, and Jarilla, that have historical significance and ecological importance; careful selection of species that are well adapted to the region's climate and soil conditions ensure a higher chance of successful establishment and long-term sustainability.

Once these native trees and shrubs take root, they will play a pivotal role in cooling the soil beneath them, fostering increased water retention and creating a more favorable environment for essential nutrients and soil microbes. As the soil improves in health, it becomes better equipped to support a flourishing ecosystem, benefitting both plant and animal life. Moreover, the complex root systems developed by the newly planted native species will act as a natural defense against rainwater runoff and soil erosion by anchoring the soil firmly in place.

The reforesting process has already commenced through a dedicated group of townsfolk under a collaborative effort known as tequio—a tradition of obligatory volunteer contribution toward community development practiced through uses and customs (usos y costumbres). In July of 2022, following several lackluster attempts at grand reforestation, members of the Enlace Foundation and Harvard met with Natalia Lazaro, the director of Agua del Espino’s school. Lazaro anxiously listened to the Foundation’s concerns and graciously offered a sizable piece of property west of the town center for a reforestation project. With contributions through tequio from parents of school children, 300 trees and 1000 agave plants were planted in careful arrangements between existing vegetation and around the fenced border of the soccer field´s perimeter. Future endeavors through tequio will establish a tree nursery at the school, reinforcing the state sponsored program sembrando vida that several campesinos started one year ago.

Livestock

In conjunction with the reforestation efforts, there are crucial discussions taking place with farmers regarding their livestock management practices. Currently, and historically, farmers have allowed their livestock to graze freely on the large swaths of communal land. However, with the steady growth of the community, remaining communal land is subject to overgrazing by livestock. Over 500 hectares of land have become dangerously depleted of their natural green cover. Furthermore, this practice of open grazing has directly hampered reforestation efforts. In 2020 and 2021, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ReThink foundation, with the help of the Harp Helu foundation, led reforestation efforts by planting over 2000 trees fence-protected areas of communal land. However, due to lack of attention and supervision of these areas, locals allowed their animals to freely graze over the land, inevitably leading to the disappearance of nearly all of the newly planted trees. Going forward, it is evident that careful livestock management is essential and must go hand in hand with the reforestation initiatives. Balancing the needs of the community, the livestock, and the environment is crucial to ensure the sustainability and health of the ecosystem.

The issue at hand is also characterized by the presence of goats in particular, which have proven to be the most detrimental animals to the landscape due to their grazing habits. Because they are not selective about their food, goats have the tendency to completely deplete the landscape of any and all plant cover. In response to this concern, INSO has engaged in discussions with the community about the possibility of transitioning from goats to sheep, as sheep are more selective in their diet and do not consume vegetation as voraciously as goats do. This shift to sheep would help mitigate the negative impact of grazing on the environment and promote a more sustainable coexistence between livestock and the delicate ecosystem of Agua del Espino.

Regenerative Agriculture

In the wild, agave plants naturally grow in close proximity to other native plants, fostering a balanced ecosystem. However, with the increasing demand for agave cultivation in the production of mezcal, farming practices adopted from tequila producers in the State of Jalisco have disrupted this natural growth process.

The encouragement of monoculture cultivation poses several environmental challenges. Farmers are regularly encouraged by non-native opportunistic entrepreneurs to remove any and all weeds that appear amidst rows of agave. This obliteration not only further distances the agaves from their natural growth patterns but exposes the soil directly to the hot sun, which encourages water evaporation rather than water sequestration. As a result, the soil tends to dry out quickly, leading to decreased moisture levels and reduced water retention capacity. Healthy microorganisms are further inhibited by poisonous pesticides similarly proposed by non-native entrepreneurs. The combination of these methods results in severe nutrient depletion and a decline in the overall health of the soil, making it less fertile and unable to support thriving vegetation.

Furthermore, the arrangement of these monoculture patches in rows parallel to the mountain peaks exacerbates the problem. When sparse rains occur, the water is channeled rapidly along these rows, encouraging paths of erosive runoff. This runoff carries away valuable topsoil together with pesticide and fertilizer additives leading to downstream environmental damage including siltation and reduced water quality.

Recognizing the importance of preserving the region's delicate ecological balance, Enlace, Rethink, INSO and Harvard, in collaboration with farmers like Don Herminio and Don Elias, have proposed a shift towards regenerative agriculture. The key to regenerative agriculture lies in planting agave in close proximity to other carefully selected plants based on the ecological needs of the land and the community's requirements. For example, milpa and fruit trees, such as Nisperos, Duraznos, and Lemons, are known to thrive in the region and offer valuable products for community members. By intercropping agave with these taller trees, the soil will benefit from shading, which helps to cool the ground and retain water. The synergy between the plants creates a thriving microenvironment that nurtures the agave while also revitalizing the overall environment.

In addition to intercropping, changing the rows of planting to be perpendicular to the slope of the mountain allows the soil and its root systems to catch and retain water instead of being channeled downhill between rows. This practice enhances water absorption and minimizes water wastage, ensuring that the precious resource is optimally utilized for the growth and well-being of trees, agave, milpa and other types of vegetation.

The traditional practices of agave cultivation and mezcal distillation are a crucial source of sustenance and livelihood for the people of Agua del Espino. However, the cultivation of agave in step with ever-increasing market pressures has left a distinct mark on the landscape. The initiatives outlined so far—water catchment, reforestation, livestock management, and regenerative agriculture—are largely focused on mitigating this footprint. The following final proposal works directly in hand with the agave distillation process, utilizing its byproducts to foster the continued sustainable growth of the ejido.

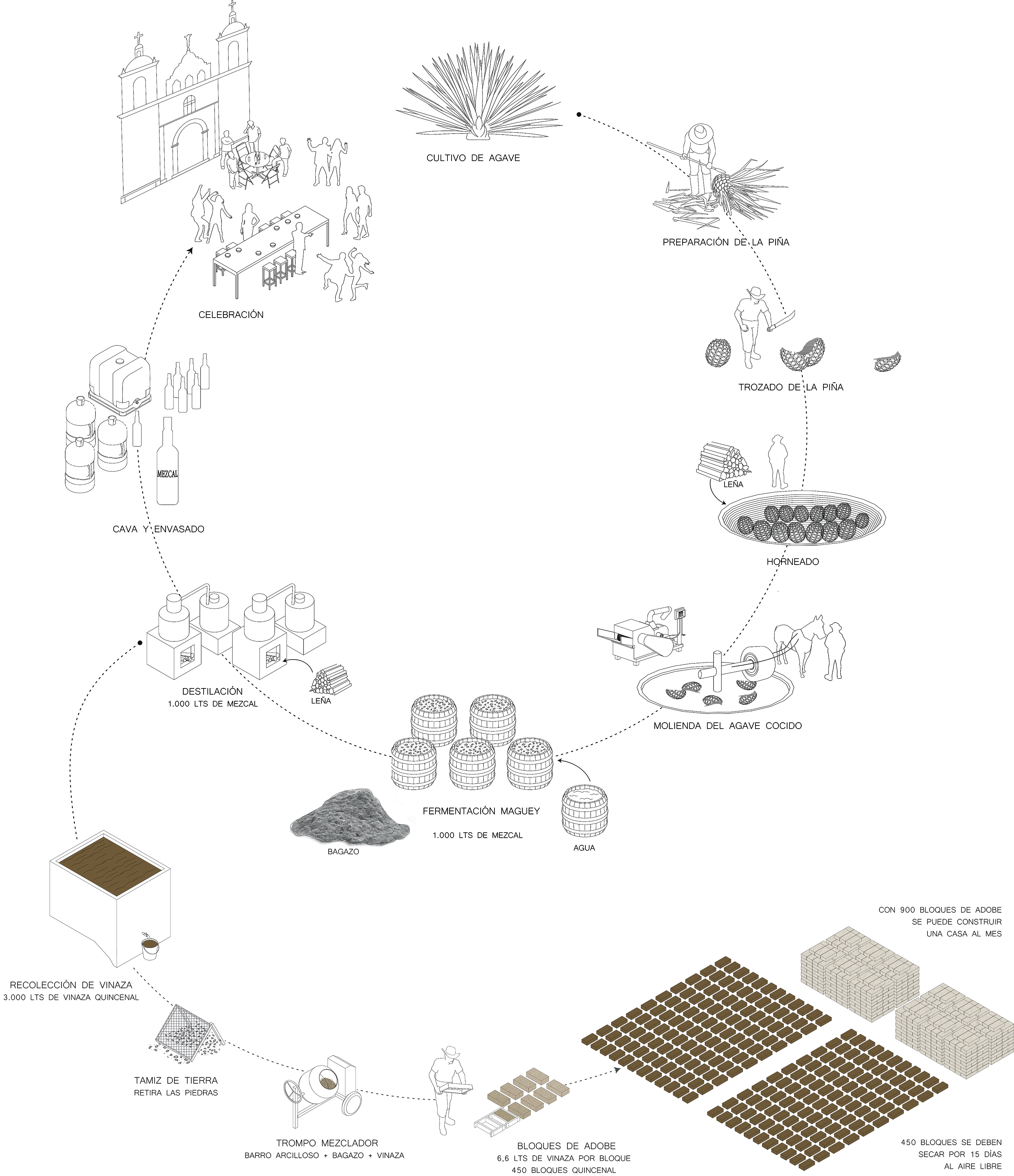

The process of agave cultivation and mezcal distillation is a taxing and complex art passed down through generations within the community of Agua del Espino. Unlike many modern industrial production methods, the mezcal of Agua del Espino maintains its small-scale artisanal roots. In 2017, the ejido housed but one mezcal maestro, which was then sufficient for all of the town’s celebratory and distributary needs. Now, in 2023, the maestros have grown in number to an environmentally demanding 13.

Indeed, market pressures continue to exert their influence on agave cultivation, primarily driven by the time-consuming nature of the process. Harvesting agave for distillation requires the entire plant to be used, and the agave plant is only viable for mezcal production once it reaches maturity, a process that takes a minimum of eight years. This prolonged maturation period places significant strain on agave farmers, who face immense challenges and financial constraints, as they may not see any return on their investments for up to a decade of dedicated cultivation.

After the agave plant is harvested, its core is roasted, crushed, and milled, then combined with water to ferment. Following several days of hard work, the once locally celebrated mezcal is bottled and shipped to market, leaving behind several byproducts. The first of these byproducts is a largely unharmful, fibrous material called bagazo. Far more problematic is the second byproduct, an acidic solution called vinaza. Under current conditions, after distillation, this acidic liquid is released into the environment and left to leach into the soil. The vinaza poisons the aquifers through acidification, which not only damages the environment but poses health risks to the townsfolk.

Rather than releasing these byproducts into the environment, an exploration led by Alejandro Montes of COAA engineered a way to give them new life. Montes led a workshop in Agua del Espino with students from the University of Toronto, encouraging them to explore the ancestral practice of making adobe bricks from organic materials. Guided by local mezcal maestro Don Hermanio, the students experienced firsthand the alchemy of turning agricultural byproducts into a sustainable building material with profound historical roots. Embracing the byproducts of mezcal distillation as part of their process, the group molded mixtures of dirt, vinaza, and bagazo into earthen adobe bricks, offering a sustainable and economically efficient solution for the rapid expansion of the ejido.

Currently, Agua del Espino is peppered with ubiquitous concrete block construction. Where earth constructions are associated with disease and poverty, concrete is viewed as a hygienic staple of the developed world. Yet, these impressions are mere assumptions of modernity, and do not account for the incredibly poor thermal performance of the concrete block in arid climates like those of Agua del Espino. Returning to earthen construction not only provides an economically efficient and environmentally sustainable alternative, but allows for far more efficient natural thermoregulation in man-made structures.

Client: Agencia Municipal Agua del Espino | Team: Rethink Foundation, Enlace Foundation, Pablo Pérez Ramos, Harvard David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies | Photography: Enlace Arquitectura, Guillermo Chavez